When heraldry began it was nearly the same all over Europe, but over the centuries specific national practices developed. The Heraldic Laws and Rules, and the history of the grant of arms, is different in Germany and the German-speaking countries in the former “Holy Roman Empire”. By the time that Empire ended in 1806 Germany was split into 7,000 (some historians say 17,000) different and independent Kingdoms, Dukedoms, Principalities, Graviates, Seigneurities (Herrschaften), Chivalric Dominions (Reichsritterschaften) and free Imperial cities. It is little wonder, therefore that there was no central authority in the matter of granting arms.

It is a legend, a fairy tale, to pretend that arms in Germany were generally granted by the Emperor. Between 1350 and around 1600 only 18 achievements of arms were granted in this way. These came with an additional grant of feudal dues and rights.

Most arms were self-styled. In the Early Middle Ages Emperor Karl IV’s Marshal of Arms Bartolus de Saxoferato (Berthold Eisensax) wrote “it is practice in the Holy Empire that everyone will use the arms he wants” [Tractatus de insignils et armis]. It is believed that about three million coats of arms were borne by German families. Only a few thousand were subsequently registered with an “Heraldic Authority” (Hofpfaltzgraf) against payment of a fee.

The Hofpfaltzgrafen

A Hofpfaltzgraf (Comes Palatinus) could be a person, a corporate body, or an organisation. Most noble families held the position as an hereditary title. Not only were the noble families Stadion, Schwarzenberg, Behaim and many others Hofpfaltzgrafen but so too were the Monastery of Brixon/Tirol, Metz, Toul, Verdun, the Council of Salzburg and the University of Vienna. The University of Vienna had the right to appoint a “Doctor Laureus” and with this appointment was connected an ennobling. The poet Friedrich von Schiller, who was probably from Weimar, was such a Doctor Laureus. Not all the Hopfaltzgrafen had the authority to confer ennoblement, but many did so nonetheless, if the fee paid was large enough. Fees for their activity had to be shared with the Emperor, and it is perhaps unsurprising that the book-keeping was not of the highest standard.

By the end of the Empire in 1806 nearly four thousand families and bodies claimed to be Hofpfaltzgrafen and Letters Patent from most of them are not worth the paper they were printed on. Out of the three million or so coats of arms mentioned previously records of less than ten per cent have survived, and of those about ninety per cent relate to noble families. More arms are known but cannot be related to a specific family. Apart from the damage caused by centuries of warfare most older Imperial era documents were recycled after the 30 Years War when parchment was scarce. Letters Patent were usually written down only as a single original, duplicate copies are very rare. The Patents should have been recorded in so-called “Libells” but they are incomplete or were recycled as well.

After 1806 the Hofpfaltzgrafen became a nominal title only, their previous powers being transferred to State Heralds Offices (Heroldsaemtern). Unfortunately these were not established everywhere, and where they did exist they confined their activities to questions of nobility and noble arms, and civic arms. (There was one exception – the Kingdom of Saxony, which granted arms to commoners from 1911.) In fact most German States had no Heralds Office, or only had one intermittently. The Kingdom of Prussia maintained one from 1888 to 1918, the Kingdom of Bavaria from 1899 to 1918, and the Kingdom of Saxony from 1806 to 1918.

The current position

Since 1918 heraldic affairs are handled under the Civil Law. Personal arms are protected as a part of the name if the bearing is officially recorded and published. For this purpose there are a number of “heraldic societies” which have to be licensed by the local Lower Court, the Revenue, and the Chamber of Commerce. The society has to be formally established and obey various rules, including keeping and publishing an armorial and keeping genealogical records for the arms it registers. It is worth noting at this point that in Germany the arms relate to a family, and so a name, and not to an individual.

The societies will review arms submitted to them according to the rules of heraldry and may demand changes to accord with the rules as a condition of registering the arms. The only sanction, however, is a refusal to register.

It is possible to register your arms through a solicitor rather than through one of the societies, but that is a problematic exercise. You would still need to publish the registered arms, and the solicitor would probably not be in a position to certify that they accorded with the rules of heraldry (if they do not comply, the arms are regarded in law as only a trade mark). This puts the societies in quite a strong moral position.

The position regarding civic arms is slightly different. Most municipal/communal constitutions provide that the town or community may use arms. If new arms are required they are designed by a heraldist or heraldry society. The arms must then be scrutinised by the State Archive, following which they become legal. A great many smaller communities bear arms which have not been through this process and are therefore “unofficial” if not “illegal”.

current arms of Germany

The heraldic rules

There are some differences between the German rules and those of, say, England, but the general principle is that a mediaeval knight should be able to join a tournament with a shield granted today without causing a sensation. Modern charges such as propellers or guns are therefore not allowed.

Because the arms belong to a family and not to an individual marks of cadency are not used. However, sometimes a branch of a family will change a tincture, add a charge, or change the crest all of which is allowed.

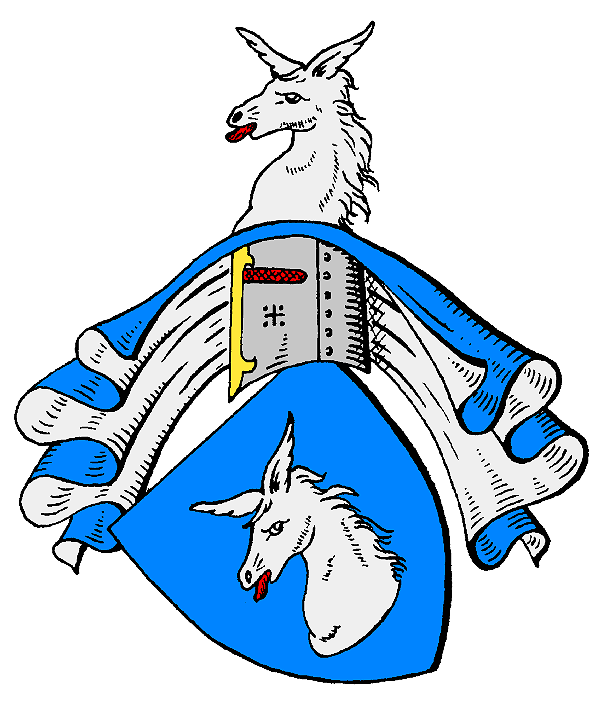

It is forbidden to use a shield divorced from the rest of the achievement because many shields on their own look alike.

Supporters may be part of an achievement without any special qualification. Examples are in the arms of von Bismarck and von Zeppelin.

There is no significance in the type of helm used. Quite often the old Imperial helm is used – gold affronty with visor open – or one with bars (restricted to Peers in England). There is no difference in German rules between an achievement of a commoner and an achievement of a noble. A coronet on the helmet sometimes indicates membership of a chivalric society or tournament faculty, but often it has no significance at all.

The helm and the shield must be of matching style – a Baroque helm requires a Baroque shaped shield. No mix and match.

A mantle or tent for the arms should only be used by a sovereign or royalty but this rule was often broken. There are many arms known (such as Graves Normann) with a mantle used by lower or untitled nobility. Some Kings and Dukes (such as the Kings of Wüttemberg) never used a tent or mantle. At the end of the 19th century it became fashionable to display commoner arms with a kind of Spanish mantilla, mostly in the tinctures of the arms but sometimes in purpure and ermine. Today a mantle or tent is used by societies or corporate bodies. The royalty and nobility in Germany mostly bear a “normal” arms with helm and crest without a rank-coronet.

A lot of heraldry rules are disputed, except the tincture rule. Different authorities (books and individuals) offer different interpretations, and it is therefore for the individual heraldist to form his opinion by research.