ORIGIN OF COATS OF ARMS

Heraldry is the science which teaches how to blazon or describe in proper terms armorial bearings and their accessories. In all ages men have made use of figures of living creatures, trees, flowers, and inanimate objects, as symbolical signs to distinguish themselves in war, or denote the bravery and courage of their chief or nation. The allegorical designs emblazoned on the standards, shields, and armour of the Greeks and Romans—the White Horse of the Saxons, the Raven of the Danes, and the Lion of the Normans, may all be termed heraldic devices.

Hereditary arms of families were first introduced at the commencement of the twelfth century. When numerous armies engaged in the expeditions to the Holy Land, consisting of the troops of twenty different nations, they were obliged to adopt some ensign or mark in order to marshal the vassals under the banners of the various leaders. The regulation of the symbols whereby the Sovereigns and Lords of Europe should be distinguished, all of whom were ardent in maintaining the honour of the several nations to which they belonged, was a matter of great nicety, and it was properly entrusted to the Heralds who invented signs of honour which could not be construed into offence, and made general regulations for their display on the banners and shields of the chiefs of the different nations. The ornaments and regulations were sanctioned by the sovereigns engaged in the Crusade, and hence the origin of the present system of Heraldry, which prevails with trifling variations in every kingdom of Europe.

The passion for military fame which prevailed at this period led to the introduction of mock battles, called Tournaments. Here the Knights appeared with the Heraldic honours conferred upon them for deeds of prowess in actual battle. All were emulous of such distinctions. The subordinate followers appeared with the distinctive arms of their Lord, with the addition of some mark denoting inferiority. These marks of honour at first were merely pieces of stuff of various colours cut into strips and sewn on the surcoat or garment worn over armour, to protect it from the effect of exposure to the atmosphere. These strips were disposed in various ways, and gave the idea of the chief, bend, chevron, &c. Figures of animals and other objects were gradually introduced; and as none could legally claim or use those honourable distinctions unless they were granted by the Kings of Arms, those Heraldic sovereigns formed a code of laws for the regulation of titles and insignia of honour, which the Sovereigns and Knights of Europe have bound themselves to protect; and those rules constitute the science of Heraldry which forms the subject of the following pages.

VARIOUS SORTS OF ARMS.

Arms are not only granted to individuals and families, but also to cities, corporate bodies and learned societies. They may therefore be classed as follows:

Arms of Dominion or Sovereignty are properly the arms of the kings or sovereigns of the territories they govern, which are also regarded as the arms of the State. Thus the Lions of England and the Russian Eagle are the arms of the Kings of England and the Emperors of Russia, and cannot properly be altered by a change of dynasty.

Arms of Pretension are those of kingdoms, provinces, or territories to which a prince or lord has some claim, and which he adds to his own, though the kingdoms or territories are governed by a foreign king or lord: thus the Kings of England for many ages quartered the arms of France in their escutcheon as the descendants of Edward III, who claimed that kingdom in right of his mother, a French princess.

Arms of Concession are arms granted by sovereigns as the reward of virtue, valour, or extraordinary service. All arms granted to subjects were originally conceded by the Sovereign.

Arms of Community are those of bishoprics, cities, universities, academies, societies, and corporate bodies.

Arms of Patronage are such as governors of provinces, lords of manors, add to their family arms as a token of their superiority, right, and jurisdiction.

Arms of Family, or paternal arms, are such as are hereditary and belong to one particular family, which none others have a right to assume, nor can they do so without rendering themselves guilty of a breach of the laws of honour punishable by the Earl Marshal and the Kings at Arms. The assumption of arms has however become so common that little notice is taken of it at the present time.

Arms of Alliance are those gained by marriage.

Arms of Succession are such as are taken up by those who inherit certain estates by bequest, entail, or donation.

SHIELDS, TINCTURES, FURS etc.

The Shield contains the field or ground whereon are represented the charges or figures that form a coat of arms. These were painted on the shield before they were placed on banners, standards, and coat armour; and wherever they appear at the present time they are painted on a plane or superficies resembling a shield.

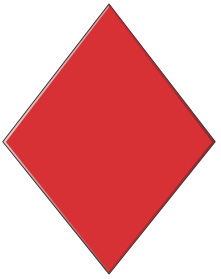

Shields in Heraldic language are called Escutcheons or Scutcheons, from the Latin word scutum. The forms of the shield or field upon which arms are emblazoned are varied according to the taste of the painter. The Norman pointed shield is generally used in Heraldic paintings in ecclesiastical buildings: the escutcheons of maiden ladies and widows are painted on a lozenge-shaped shield.

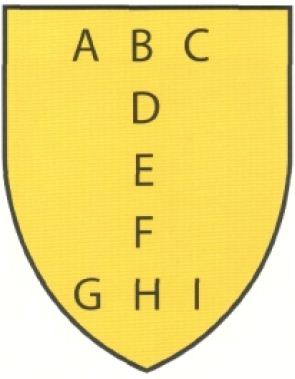

Armorists distinguish several points in the escutcheon in order to determine exactly the position of the bearings or charges. They are denoted in the annexed diagram, by the first nine letters of the alphabet ranged in the following manner:

A, the dexter chief.

B, the precise middle chief.

C, the sinister chief.

D, the honour point.

E, the fess point.

F, the nombril point.

G, the dexter base.

H, the precise middle base.

I, the sinister base.

The dexter side of the escutcheon answers to the left hand, and the sinister side to the right hand of the person that looks at it.

TINCTURES

By the term Tincture is meant that variable hue which is given to shields and their bearings; they are divided into colours and furs.

The colours or metals used in emblazoning arms are:

These colours are denoted in engravings by various lines or dots, as follows:

OR, which signifies gold, and in colour yellow, is expressed by dots.

ARGENT signifies silver or white: it is left quite plain.

GULES sig. red: it is expressed by lines drawn from the chief to the base of the shield.

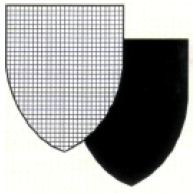

AZURE sig. blue: represented by lines drawn from the dexter to the sinister side of the shield, parallel to the chief.

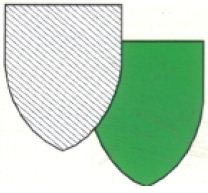

VERT signifies green: it is represented by slanting lines, drawn from the dexter to the sinister side of the shield.

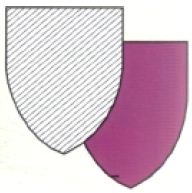

PURPURE, or purple, is expressed by diagonal lines, drawn from the sinister to the dexter side of the shield.

SABLE or black, expressed by horizontal and perpendicular lines crossing each other.

TENNE, which is tawny, or orange colour, is marked by diagonal lines drawn from the sinister to the dexter side of the shield, traversed by perpendicular lines from the chief.

SANGUINE, dark red, murrey, represented by diagonal lines crossing each other.

In addition to the foregoing tinctures, there are nine roundlets or balls used in Armory, the names of which are sufficient to denote their colour without expressing the same:BEZANT, Or; PLATE, Argent; HURTS, Azure; TORTEAUX, Gules; GOLPE, Purpure; PELLET, Sable; ORANGE, Tenne; GUZES, Sanguine; POMEIS, Vert

FURS

Furs are used to ornament garments of state and denote dignity: ther are used in Heraldry, not only for the lining of mantles and other ornaments of the shield, but also as bearings on escutcheons.

WHITE, represented by a plain shield, like argent.

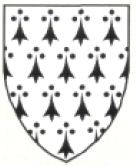

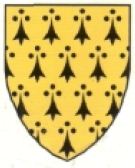

ERMINE—white powdered with black tufts.

ERMINES—field sable, powdering argent.

ERMINOIS—field or, powdering sable.

PEAN—field sable; powdering or.

ERMYNITES—Argent, powdered sable, with the addition of a single red hair on each side the sable tufts. This fur is seldom seen in English heraldry; and it is impossible to give an example without using colour.

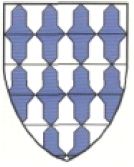

VAIR—argent and azure. It is represented by small bells, part reversed, ranged in lines in such a manner, that the base argent is opposite to the base azure.

COUNTER-VAIR, the bells are placed base against base and point against point.

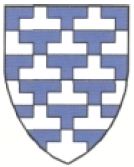

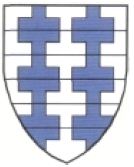

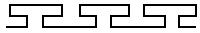

POTENT an obsolete word for a crutch. The field is filled with small potents, ranged in lines, azure and argent.

POTENT COUNTER-POTENT, the heads of the crutches or potents touch each other in the centre of the shield.

LINES USED IN PARTING THE FIELD

Escutcheons that have more than one tincture are divided by lines; the straight lines are either perpendicular |, horizontal —, diagonal line dexter \, and diagonal line sinister /.

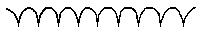

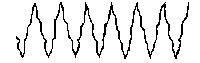

Curved and angular lines are numerous, and each has an Heraldic name expressive of its form. The names and figures of those most commonly used by English armorists are as follow:

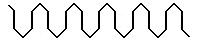

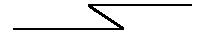

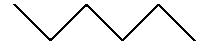

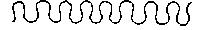

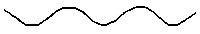

Engrailed

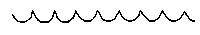

Radient

Urdee

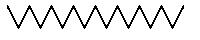

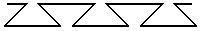

Indented

Invected

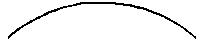

Arched

Doublearched

Potent

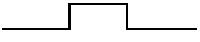

Embattledgrady

Dovetailed

Nowy

Escartelle

Bevilled

Angled

Dancette

Embattled

Nebule

Wavy

If a shield is divided into four equal parts, it is said to be quartered: this may be done two ways, viz.

QUARTERED PER CROSS,the shield is divided into four parts, called quarters, by an horizontal and perpendicular line, crossing each other in the centre of the field, each of which is numbered.

QUARTERED PER SALTIER, which is made by two diagonal lines, dexter and sinister, crossing each other in the centre of the field.

The Escutcheon is sometimes divided into a great number of parts, in order to place in it the arms of several families to which one is allied; this is called a genealogical achievement. The compartments are called QUARTERINGS.

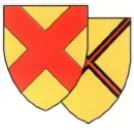

DIFFERENCES

All members of the same family claim the same bearings in their coats of arms; and to distinguish the principal bearer from his descendants or relatives, it was necessary to invent some sign so that the degree of consanguinity might be known. These signs are called DIFFERENCES. During the Crusades, the only difference consisted in the bordure or border, which, as the name implies, was a border or edging running round the edge of the shield. The colour and form of this border served to distinguish the leaders of the different bands that served under one duke or chieftain. The same difference might be used to denote a diversity between particular persons descended from one family. At the present time they are not used to denote a difference, but as one of the ordinaries to a coat of arms. The annexed example exhibits the arms of the Monastery of Bermondsey. Party per pale, azure and gules; a bordure, argent. This bordure is plain; but they may be formed by any of the foregoing lines.

The annexed example is a bordure gules.

The differences used by armorists at the present time are nine in number. They not only distinguish the sons of one family, but also denote the subordinate degrees in each house.

Should either of the nine brothers have male children, the eldest child would place the label on the difference that distinguished his father; the second son would place the crescent upon it; the third the mullet; continuing the same order for as many sons as he may have.

All the figures denoting differences are also used as perfect charges on the shield; but their size and situation will sufficiently determine whether the figure is used as a perfect coat of arms, or is introduced as a difference or dimunition.

Sisters have no differences in their coats of arms. They are permitted to bear the arms of their father, as the eldest son does after his father’s decease.

The only abatement used in heraldry is the baton: this denotes illegitimacy. It is borne in the escutcheons of the dukes that assume the royal arms as the illegitimate descendants of King Charles the Second.

HONOURABLE ORDINARIES

Honourable ordinaries are the original marks of distinction bestowed by sovereigns on subjects that have become eminent for their services, either in the council or the field of battle. It is sufficient to know that they are merely broad lines or bands of various colours, which have different names, according to the place they occupy in the shield; ancient armorists admit but nine honourable ordinaries—the chief, the pale, the bend, the bend sinister, the fess, the bar, the chevron, the cross, and the saltier.

The chief is an ordinary terminated by an horizontal line, which, if it is of any other form but straight, its form must be expressed; it is placed in the upper part of the escutcheon, and occupies one third of the field.

Any of the lines before described may be used to form the chief.

The chief has a diminutive called a fillet; it must never be more than one fourth the breadth of the chief.

This ordinary may be charged with a variety of figures, which are always named after the tincture of the chief.

It may be necessary to inform the reader that, in describing a coat of arms, the general colour of the shield or the field is first described, then the honourable ordinaries, their tinctures, then the object with which they are charged. We shall have to remark more particularly on the order of describing ordinaries, tinctures, and charges on coats of arms, when we treat of the rules of heraldry; but the student might have been confused if this brief direction had been omitted, as we shall have to describe every shield of arms in the same order.

The pale is an honourable ordinary, consisting of two perpendicular lines drawn from the top to the base of the escutcheon, and contains one third of the width of the field.

The pale may be formed of any of the lines before described; it is then called a pale engrailed, a pale dancette etc.

The pale has a diminutive called the pallet, which is one half the width of the pale.

The pale has another diminutive one fourth its size; it is called an endorse.

The pale and the pallet may receive any charge; but the endorse is never to be charged with any thing.

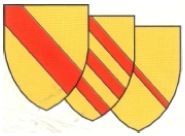

The bend is an honourable ordinary, formed by two diagonal lines drawn from the dexter chief to the sinister base, and contains the fifth part of the field if uncharged; but if charged with other figures, the third part of the field.

The bend has four diminutives, viz. the garter which is half the breadth of the bend.

The cotice which is the fourth part of the bend. Cotices generally accompany the bend in pairs; thus a bend between two cotices is said to be cotised.

The riband, which is one third less than the garter and the bendlet, must never occupy more than one sixth of the field.

The bend sinister is the same breadth as the bend dexter, and is drawn from the sinister to the dexter side of the shield.

The scarpe is the diminutive of the bend sinister, and is half its size.

The baton is the fourth part of the bend, and, as before mentioned, it is a mark of illegitimacy, and seldom used in Heraldry, but by the illegitimate descendants of royalty.

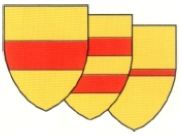

The fess is formed by two horizontal lines drawn above and below the centre of the shield. The fess contains in breadth one third of the field.

The bar is formed in the same manner as the fess, but it only occupies the fifth part of the field. It differs from the fess, that ordinary being always placed in the centre of the field; but the bar may be placed in any part of it, and there may be more than one bar in an escutcheon.

The closet is a diminutive of the bar, and is half its width.

The barrulet is half the width of the closet.

The annexed example is to illustrate the word gemels, which is frequently used to describe double bars. The word gemels is a corruption of the French word jumelles, which signifies double.

When the shield contains a number of bars of metal and colour alternate, exceeding five, it is called barry of so many pieces, expressing their numbers.

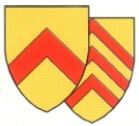

The figure of the chevron has been described as representing the gable of a roof. It is a very ancient ordinary, and the less it is charged with other figures the more ancient and honourable it appears.

The diminutives of the chevron, according to English Heraldry, are the chevronel, which is half the breadth of the chevron.

And the couple-close, which is half the chevronel.

Braced is sometimes used for interlaced. See the word BRACED in the Dictionary.

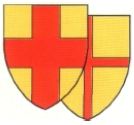

This, as its name imports, was the distinguishing badge of the Crusaders, in its simplest form. It was merely two pieces of list or riband of the same length, crossing each other at right angles. The colour of the riband or list denoted the nation to which the Crusader belonged. The cross is an honourable ordinary, occupying one fifth of the shield when not charged, but if charged, one third.

When the cross became the distinguishing badge of different leaders in the Crusades, the simple form given in the preceding example was not generally adopted. Some bordered the red list with a narrow white edge, others terminated the arms of the cross with short pieces of the same colour, placed transversely, making each arm of the cross have the appearance of a short crutch; the ends of these crutches meeting in a point, make the cross potent. There is so great a variety of crosses used in Heraldry that it would be impossible to describe them within the limits of this introduction to Heraldry. Small crosses borne as charges are called crosslets.

The saltier was formed by making two pieces of riband cross diagonally, having the appearance of the letter X, or, speaking heraldically, the bend and bend sinister crossing each other in the centre of the shield. The saltier, if uncharged, occupies one-fifth of the field; if charged, one-third.

Like the cross, the saltier may be borne engrailed, wavy, and the termination of the arms of the saltier varied; but there are not so many examples of the variation of the form in the saltier as in the cross.

SUBORDINATE ORDINARIES

In order more particularly to distinguish the subordinates in an army (the chieftains of different countries alone being entitled to the preceding marks of honour), other figures were invented by ancient armorists, and by them termed subordinate ordinaries. Their names and forms are as follows:

The gyron is a triangular figure formed by drawing a line from the dexter angle of the chief of the shield to the fess point, and a horizontal line from that point to the dexter side of the shield.

The field is said to be gyrony when it is covered with gyrons.

The canton is a square part of the escutcheon, usually occupying about one-eighth of the field; it is placed over the chief at the dexter side of the shield: it may be charged, and when this is the case, its size may be increased. The canton represents the banner of the ancient Knights Banneret.

The lozenge is formed by four equal and parallel lines but not rectangular, two of its opposite angles being acute, and two obtuse.

The fusil is narrower than the lozenge, the angles at the chief and base being more acute, and the others more obtuse.

The mascle is in the shape of a lozenge but perforated through its whole extent except a narrow border.

The fret is formed by two lines interlaced in saltier with a mascle.

Fretty is when the shield is covered with lines crossing each other diagonally and interlaced.

At the present time it is not usual to name the number of pieces, but merely the word fretty.

The pile is formed like a wedge, and may be borne wavy, engrailed, etc.; it issues generally from the chief, and extends towards the base, but it may be borne in bend or issue from the base.

The inescutcheon is a small escutcheon borne within the shield.

An orle is a perforated inescutcheon, and usually takes the shape of the shield whereon it is placed.

The flanche is formed by two curved lines nearly touching each other in the centre of the shield.

In the flasque the curved lines do not approach so near each other.

In the voider the lines are still wider apart; this ordinary occupies nearly the whole of the field: it may be charged.

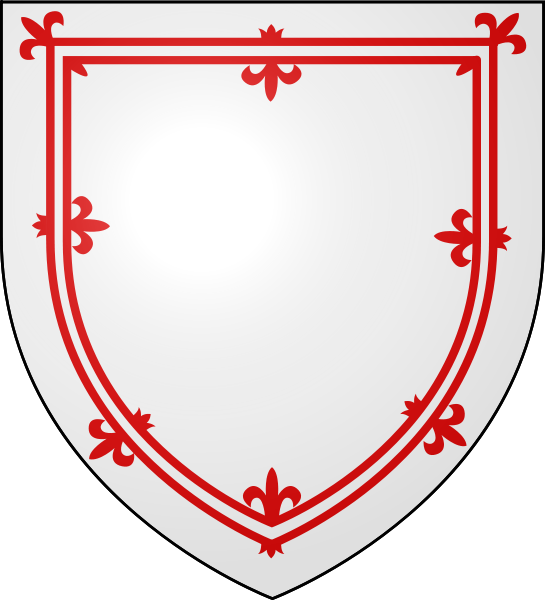

The tressure is a border at some distance from the edge of the field, half the breadth of an orle: the tressure may be double or treble.

Tressures are generally ornamented, or borne flory or counter flory as in the annexed example.

CHARGES BORNE IN COATS OF ARMS

At first when the Feudal System prevailed none but military chieftains bore Coats of Arms. And as few persons held land under the Crown but by military tenure, that is, under the obligation of attending in person with a certain number of vassals and retainers when their services were required by the king for the defence of the state, heraldic honours were confined to the nobility, who were the great landholders of the kingdom. When they granted any portion of their territory to their knights and followers as rewards for deeds of prowess in the field or other services, the new possessors of the land retained the arms of their patrons with a slight difference to denote their subordinate degree. The knights assumed the privilege of choosing any device they pleased to ornament the crests of their helmets in the field of battle, or in the mock combat of the tournament. The knight was known and named from the device used as his crest. Thus the heralds, in introducing him to the judges of the field called him the Knight of the Swan, the Knight of the Lion, without mentioning any other title. In two or three generations the bearer of the arms established his right to a new crest, and the heralds, to preserve the memory of the ancient honour of the family, introduced the old crest into the coat of arms, either as a charge upon the principal ordinary, or on an unoccupied part of the field.

The sovereigns of Europe, in order to decrease the power of the great barons, bestowed estates and titles not only for deeds of arms, but wisdom in council, superior learning and other qualities.

THE EXTERNAL ORNAMENTS OF ESCUTCHEONS

The ornaments that accompany or surround escutcheons were introduced to denote the birth, dignity, or office of the person to whom the coat of arms belongs. Over regal escutcheons are placed the crown which pertains to the nation over which the sovereign presides. The crown is generally surmounted with a crest: as in the arms of the kings of England, the crown is surmounted by a lion statant, guardant, crowned.

Over the Papal arms is placed a tiara or triple crown, without a crest.

Above the arms of archbishops and bishops the mitre is placed instead of a crest.

Coronets are worn by all princes and peers. They vary in form according to the rank of the nobleman. There are crowns of dukes, marquises, earls, viscounts, barons etc.

Helmets are placed over arms, and show the rank of the person to whom the arms belong: by the metal of which they are made, by their form and by their position.

Mantlings were the ancient coverings of helmets to preserve them and the bearers from the injuries of the weather. It is probable that they were highly ornamented with scroll-work of gold and silver, and their borders or edges cast into fanciful shapes. They are now formed into scroll-work proceeding from the sides of the helmet, and are great ornaments to an escutcheon.

A chapeau is an ancient hat or rather cap of dignity worn by dukes. They were formed of scarlet velvet and turned up with fur. They are frequently used instead of a wreath under the crests of noblemen and even gentlemen.

The wreath was formed by two large skeins of silk of different colours twisted together. This was worn at the lower part of the crest, not alone as an ornament, but to protect the head from the blow of a mace or sword. In Heraldry the wreath appears like a straight line or roll of two colours generally the same as the tinctures of the shield. The crest is usually placed upon the wreath. The crest is the highest part among the ornaments of a coat of arms. It is called crest from the Latin word crista, which signifies comb or tuft. Crests were used as marks of honour long before the introduction of Heraldry. The helmets and crests of the Greek and Trojan warriors are beautifully described by Homer. The German heralds pay great attention to crests and depict them as towering to a great height above the helmet. Knights who were desirous of concealing their rank, or wished particularly to distinguish themselves either in the battle field or tourney, frequently decorated their helmets with plants or flowers, chimerical figures, animals etc.

The difference between crests and badges as heraldic ornaments is that the former are always placed on a wreath, in the latter they are attached to the helmet.

The scroll is a label or ribbon containing the motto, it is usually placed beneath the shield and supporters.

MARSHALLING CHARGES ON ESCUTCHEONS BY THE RULES OF HERALDRY

The symbolic figures of Heraldry are so well known to those acquainted with the science in every kingdom of Europe, that if an Englishman was to send a written emblazonment or description of an escutcheon to a French, German or Spanish artist acquainted with the English language, either of them could return a properly drawn and coloured escutcheon; but a correct emblazonment would be indispensable. A single word omitted would spoil the shield.

I

In emblazoning an escutcheon, the colour of the field is first named; then the principal ordinary, such as the fess, the chevron, etc., naming the tincture and form of the ordinary; then proceed to describe the charges on the field, naming their situation, metal or colour; lastly, describe the charges on the ordinary.

II

When an honourable ordinary or some one figure is placed upon another, whether it be a fess, chevron, cross, etc., it is always to be named after the ordinary or figure over which it is placed, with either the words surtout or overall.

III

In the blazoning such ordinaries as are plain, the bare mention of them is sufficient; but if an ordinary should be formed of any of the curved or angular lines, such as invected, indented, etc., the lines must be named.

IV

When a principal figure possesses the centre of the field, its position is not to be expressed; it is always understood to be in the middle of the shield.

V

When the situation of a principal bearing is not expressed, it is always understood to occupy the centre of the field.

VI

The number of the points of mullets must be specified if more than five, also if a mullet or any other charge is pierced, it must be mentioned.

VII

When a ray of the sun or other single figure is borne in any other part of the escutcheon than the centre, the point it issues from must be named.

VIII

The natural colour of trees, plants, fruits, birds, etc., is to be expressed in emblazoning by the word proper; but if they vary from their natural colour, the tincture or metals that is used must be named.

IX

Two metals cannot come in contact: thus or, cannot be placed on argent, but must be contrasted with a tincture.

X

When there are many figures of the same species borne in coats of arms, their number must be observed as they stand, and properly expressed. The annexed arrangements of roundlets in shields will show how they are placed and described.

The two roundlets are arranged in pale, but they may appear in chief or base; or in fess.

Three roundlets, two over one; if the single roundlet had been at the top, it would have been called one over two.

Three roundlets in bend. They might also be placed in fess, chief, base, or in pale.

Four roundlets, two over two. Some armorists call them cantoned as they form a square figure.

Five roundlets; two, one, two, in saltier.

Five roundlets; one, three, one, or in cross.

Six roundlets; two, two, two, paleway.

Six roundlets; three, two, one, in pile.

There are seldom more figures than seven, but no matter the number; they are placed in the same way, commencing with the figures at the top of the shield, or in chief. If the field was strewed all over with roundlets, this would be expressed by the word semé.

Marshalling coats of arms is the act of disposing the arms of several persons in one escutcheon, so that their relation to each other may be clearly marked.

In Heraldry, the husband and wife are called baron and femme; and when they are descended from distinct families, both their arms are placed in the same escutcheon, divided by a perpendicular line through the centre of the shield. As this line runs in the same direction, and occupies part of the space in the shield appropriated to the ordinary called the pale, the shield is in heraldic language said to be parted per pale. The arms of the baron (the husband) are always placed on the dexter side of the escutcheon; and the femme (the wife) on the sinister side.

If a widower marries again, the arms of both his wives are placed on the sinister side, which is parted per fess; that is, parted by an horizontal line running in the direction of the fess, and occupying the same place. The arms of the first wife are placed in the upper compartment of the shield, called the chief; the arms of the second wife in the lower compartment, called the base. The same rule would apply if the husband had three or more wives; they would all be placed in the sinister division of the shield.

Where the baron marries an heiress, he does not impale his arms with hers, as in the preceding examples, but bears them in an escutcheon of pretence in the centre of the shield, showing his pretension to her lands in consequence of his marriage with the lady who is legally entitled to them. The escutcheon of pretence is not used by the children of such marriage; they bear the arms of their father and mother quarterly, and so transmit them to posterity.

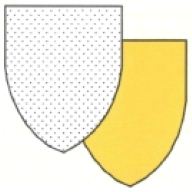

If a peeress in her own right, or the daughter of a peer, marries a private gentleman, their coats of arms are not conjoined paleways, as baron and femme, but are placed upon separate shields by the side of each other; they are usually inclosed in a mantel, the shield of the baron occupying the dexter side of the mantel, that of the femme the sinister; each party has a right to all the ornaments incidental to their rank. The femme claiming the arms of her father, has a right to his supporters and coronet. The baron, who only ranks as an esquire, has no right to supporters or coronet, but exhibits the proper helmet, wreath and crest. The peeress, by marrying one beneath her in rank, confers no dignity on her husband, but loses none of her own. She is still addressed as “your ladyship,” though her husband only ranks as a gentleman; and it is for this reason that the arms cannot be conjoined in one shield as baron and femme.

In the arms of the femme joined to the paternal coat of the baron, the proper differences by which they were borne by the father of the lady must be inserted.

If the arms of the baron has a bordure, that must be omitted on the sinister side of the shield.

Archbishops and bishops impale the paternal arms with the arms of the see over which they preside, placing the arms of the bishopric on the dexter, and their paternal arms on the sinister side of the shield; a bishop does not emblazon the arms of his wife on the same shield with that which contains the arms of the see, but on a separate shield.

Arms of augmentation are usually placed on a canton in the dexter chief of the shield; in some cases they occupy the whole of the chief. The mark of distinction denoting a baronet is usually placed on an escutcheon, on the fess point of the shield.

The rules here laid down apply to funeral atchievements, banners, etc. The only difference is that the ground of the hatchment is black round the arms of the deceased and white round the arms of the survivor.